Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Harun al Rashid

It was a moment in history when the Islamic civilization opened its doors to new ideas from the East and from the West. The confident Muslims took these ideas and remolded them in a uniquely Islamic mold. Out of this caldron came Islamic art, architecture, astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, medicine, music, philosophy and ethics. Indeed the very process of Fiqh and its application to societal problems was profoundly influenced by the historical context of the times.

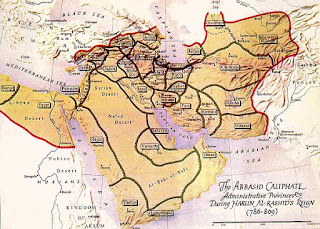

Harun al Rashid was the son of al Mansur and was the fourth in the Abbasid dynasty. Ascending the throne as a young man of twenty-two in the year 786, he immediately faced internal revolts and external invasion. Regional revolts in Africa were crushed, tribal revolts from the Qais and Quzhaa in Egypt were contained and sectarian revolts from the Alavis were controlled. The Byzantines were held at bay and forced to pay tribute. For 23 years he ruled an empire that had welded together a broad arc of the earth extending from China, bordering India and Byzantium through the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean. Herein men, material and ideas could flow freely across continental divides. However, Harun is remembered not for his empire building, but for building the edifice of a brilliant civilization.

It was the golden age of Islam. It was not the fabulous wealth of the empire or the fairy tales of the Arabian Nights that made it golden; it was the strength of its ideas and its contributions to human thought. As the empire had grown, it had come into contact with ideas from classical Greek, Indian, Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Hindu civilizations. The process of translation and understanding of global ideas was well under way since the time of al Mansur. But it received a quantum boost from Harun and Mamun.

Harun established a School of translation Bait ul Hikmah (house of wisdom) and surrounded himself with men of learning. His administration was in the hands of viziers of exceptional capabilities, the Bermecides. His courtiers included great juris doctors, poets, musicians, logicians, mathematicians, writers, scientists, men of culture and scholars of Fiqh. Ibn Hayyan (d. 815), who invented the science of chemistry, worked at the court of Harun. The scholars who were engaged in the work of translation included Muslims, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and Hindus. From Greece came the works of Socrates, Aristotle, Plato, Galen, Hippocratis, Archimedes, Euclid, Ptolemy, Demosthenes and Pythagoras. From India arrived a delegation with the Siddhanta of Brahmagupta, Indian numerals, the concept of zero and Ayurvedic medicine. From Chin came the science of alchemy and the technologies of paper, silk and pottery. The Zoroastrians brought in the disciplines of administration, agriculture and irrigation. The Muslims learned from these sources and gave to the world algebra, chemistry, sociology and the concept of infinity.

What gave the Muslims the confidence to face other civilizations was their faith. With a confidence firmly rooted in revelation, the Muslims faced other civilizations, absorbing that which they found valid and transforming it in the image of their own belief. The Qur’an invites men and women to learn from nature, to reflect on the patterns therein, to mold and shape nature so that they may inculcate wisdom. ”We shall show them our Signs on the horizon and within their souls until it is manifest unto them that it is the Truth” (Qur’an, 41:53). It is during this period that we see the emergence of the archetype of classical Islamic civilization, namely the Hakim (meaning, a person of wisdom). In Islam, a scientist is not a specialist who looks at nature from the outside, but a man of wisdom who looks at nature from within and integrates his knowledge into an essential whole. The quest of the Hakim is not just knowledge for the sake of knowledge but the realization of the essential Unity that pervades creation and the interrelationships that demonstrate the wisdom of God.

What Harun started, his son Mamun sought to complete. Mamun was a scholar in his own right, had studied medicine, Fiqh, logic and was a Hafiz e Qur’an. He sent delegations to Constantinople and the courts of Indian and Chinese princes asking them to send classical books and scholars. He encouraged the translators and gave them handsome rewards. Perhaps the story of this period is best told by the great men of the era. The first philosopher of Islam, al Kindi (d. 873), worked at this time in Iraq. The celebrated mathematician al Khwarizmi (d. 863) worked at the court of Mamun. Al Khwarizmi is best known for the recurring method of solving mathematical problems, which is used even today and is called algorithms. He studied for a while in Baghdad and is also reported to have traveled to India. Al Khwarizmi invented the word algebra (from the Arabic word j-b-r, meaning to force, beat or multiply), introduced the Indian numeral system to the Muslim world (from where it traveled to Europe and became the “Arabic” numeral system), institutionalized the use of the decimal in mathematics and invented the empirical method (knowledge based on measurement) in astronomy. He wrote several books on geography and astronomy and cooperated in the measurement of the distance of an arc across the globe. The world celebrates the name of Al Khwarizmi to this day by using “algorithms” in every discipline of science and engineering.

It was the intellectual explosion created at the time of Harun and Mamun that propelled science into the forefront of knowledge and made Islamic civilization the beacon of learning for five hundred years. The work done by the translation schools of Baghdad made possible the later works of the physician al Razi (d. 925), historian al Masudi (d. 956), the physician Abu Ali Sina (d. 1037), the physicist al Hazen (d.1039), the historian al Baruni (d. 1051), the mathematician Omar Khayyam (d.1132) and the philosopher Ibn Rushd (d.1198).

The age of Harun and Mamun was also an age of contradictions. Indeed, no other period in Islamic history illustrates with such clarity the schizophrenic attitude of Muslims towards their own history, as does the age of Harun and Mamun. On the one hand, Muslims take pride in its accomplishments. On the other, they reject the values on which those achievements were based. Muslims exude great pride in the scientists and philosophers of the era, especially in their dialectic with the West. But they reject the intellectual foundation on which these scientists and philosophers based their work.

The age of Harun and Mamun was the age of reason. Mamun, in particular, took the rationalists in full embrace. The Mu’tazilites were the rational arm of Islam. Mamun made Mu’tazilite doctrines the official court dogma. However, the Mu’tazilites were not cognizant of the limits of the rational method and overextended their reach. They even applied their methodology to the Divine Word and came up with the doctrine of “createdness” of the Qur’an. In simplified terms, this is the error one falls into when a hierarchy of knowledge is built wherein reason is placed above revelation. The Mu’tazilites applied their rational tools to revelation without sufficient understanding of the phenomenon of time or its relevance to the nature of physics. In the process, they fell flat on their face. Instead of owning up to their errors and correcting them, they became defensive and became increasingly oppressive in forcing their views on others.

Mamun’s successors applied the whip with increasing fervor to enforce conformity with the official dogma. But the ulema would not buy the theory that the Qur’an was created. Imam Hanbal fought a lifelong battle with Mamun on this issue and was jailed for over twenty years. Any idea that compromised the transcendence of the Qur’an was unacceptable to Imam Hanbal. Faced with determined opposition, the Mu’tazilite doctrine was repudiated by Caliph Mutawakkil (d. 861). Thereafter, the rationalists were tortured and killed and their properties confiscated. Al Ashari (d. 936) and his disciples tried to reconcile the rational and transcendental approaches by suggesting a “theory of occasionalism”. The Asharite ideas got accepted and were absorbed into the Islamic body politic and have continued to influence Muslim thinking to this day. The intellectual approach of the rationalists, philosophers and scientists was forsaken and sent packing to the Latin West where it was embraced with open arms and was used to lay the foundation of the modern global civilization.

Thus it was that the Muslim world came upon rational ideas, adopted them, experimented with them and finally threw them out. The historical lesson of the age of Harun and Mamun is that a fresh effort must be made to incorporate philosophy and science within the framework of Islamic civilization based on Tawhid. The issue is one of constructing a hierarchy of knowledge wherein the transcendence of revelation is preserved in accordance with Tawhid, but wherein reason and the free will of man are accorded honor and respect. The Mu’tazilites were right in claiming that man was the architect of his own fortunes but they erred in asserting that human reason has a larger reach than the Divine Word. Humankind is not autonomous. The outcome of human effort is a moment of Divine Grace. No person can predict with certainty the outcome of an action. The Asharites were right in postulating that at each moment of time Divine Grace intervenes to dispose of all affairs. But they were not correct in limiting the power of human free will. Human reason and human free will are endowed with the possibility of infinity, but this infinity collapses (fana) before the infinity of Divine transcendence.

Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD

Source : https://historyofislam.com/contents/the-classical-period/harun-al-rashid/

The ticking time bomb waiting to explode western interests in Syria

It’s becoming clearer and clearer that western involvement in the Syrian conflict began as a covert attempt to overthrow the Assad regime by arming his largely Islamist opponents.

But whatever its beginnings, the west’s focus turned definitively towards Daesh (Isis/Isil) from 2014 onwards, when the jihadi group made it very clear that western nations were just as much the enemy as Assad. And this altered focus would soon place western governments on a political collision course with one of their key NATO allies – Turkey.

The current Turkish regime has long been a time bomb waiting to explode, threatening collateral damage across the Middle East. But only recently has its ticking become too loud for the world to ignore. And what’s perhaps most worrying for western governments is that Ankara is now forming ever closer links with their arch-rivals in Russia.

It’s taken Ankara and Moscow a while to get to this point, though.

Tense Russo-Turkish relations

In November 2015, Turkey shot down a Russian jet in what would be a key moment for both the Syrian conflict and Turkey’s standing in the international community. Tensions soon escalated, and Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke of Turkey’s oil links to Daesh, referred to the country’s regime as “terrorists’ accomplices”, and placed strong sanctions on Turkish tourism and businesses. Turkish exports to Russia allegedly fell by 60.5% in the first half of 2016 (compared to the same period in 2015).

At the same time, Russia allegedly coordinated a number of airstrikes with the secular Kurdish-led ground forces of Rojava (northern Syria) – which was a big blow for Turkish-backed Islamist forces in Syria. It also opened up diplomatic relations with Rojava (a region upon which Turkey has long imposed a brutal blockade), calling for Rojavan representatives to attend Syria’s peace talks.

But with Turkey’s western allies increasingly distancing themselves from a regime in Ankara which was increasingly curtailing human rights, attacking media outlets, and massacring its own citizens, the stage was set for a change in tactics. (Even more so when we consider that the USA was also ramping up its temporary support for Rojavan militias in their efforts to defeat Daesh on the ground in Syria.)

Turkey’s change in tactics

In early July, Ankara hinted at its openness to make deals with the regimes in both Moscow and Damascus – which it had previously opposed – in an apparent attempt to stem Rojava’s influence in the region and show its opposition to the western-backed advances made on jihadi territory by Rojavan militias.

The Turkish regime was also seeking to clean up its image in general, almost a year after nose-diving into a destructive and self-indulgent civil war on its Kurdish communities, by replacing its prime minister in May. This didn’t only mean moving closer to Russia and Syria, but also to Israel and Egypt.

Then, on 15 July, a section of the Turkish army launched an abortive coup against its own government. The coup plotters claimed they wanted to “reinstall the constitutional order, democracy, human rights and freedoms” in Turkey.

While western leaders quickly condemned the coup attempt, a pro-government newspaper in Turkey soon accused the USA of orchestrating it. And these media-fuelled suspicions would further strengthen a growing current of anti-Americanism in Turkey, giving Ankara even more reason to distance itself from its allies in Washington.

A budding relationship

Even though Putin has previously slammed Turkey’s links with jihadis in Syria, the economic benefits of a renewed Russian alliance with Ankara (there are currently two major joint energy projects on hold) have clearly played a part in pushing the two powers to resolve their differences. Plus, Putin’s political pragmatism is notorious, and he’s always ready to jump at any opportunity to step in where the west is unwilling to go.

On 9 August, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Russia, on his first foreign visit since July’s coup. The groundwork for restored relations had already been laid, with Erdoğan allegedly apologising to Russia back in June and Putin expressing support for Erdoğan’s regime after the coup. And duly, Erdoğan asserted in St Petersburg on 9 August that:

the Moscow-Ankara friendship axis will be restored.

Putin, meanwhile, insisted that he would phase out sanctions on Turkey “step by step”.

According to retired Swedish Ambassador and Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies fellow Michael Sahlin:

the symbolic nature of this visit within weeks of the botched coup is far from lost on those in the US and EU who are searching for signs of possible permanent policy change [in Turkey]… To the delight of President Putin, Mr Erdogan is presumably happy to keep the West wondering, and sweating, for now.

The impact for Syria

Turkey has been at the forefront of western-backed efforts to overthrow the Assad regime in Syria ever since 2011. And its hostility to the biggest secular forces in Syria – the Kurdish-led militias of Rojava – has contributed significantly to the fact that around 60% of anti-Assad fighters today are thought to have similar extremist views to Daesh.

Renewed relations with Russia may push Turkey further away from supporting jihadis and closer to supporting a political settlement in Syria. This would likely lead to some sort of truce between the Assad regime and Turkish-backed Islamists. But it would also mean the sidelining of the secular, multi-ethnic and gender-egalitarian forces of Rojava – which the Turkish regime opposes with a passion. And that would not be good news for democracy in Syria.

A budding friendship between Putin and Erdoğan and a further distancing between NATO allies, meanwhile, could lead to Turkey’s exit from the alliance. If this happened, western governments would lose the influence they have been desperately seeking in Syria since 2011 – mostly through their links with Turkey. Ankara, on the other hand, would increase its influence in the region. And judging by its treatment of its own citizens, and its longstanding links with jihadis in Syria, that would almost certainly lay a minefield of further problems.

But whatever happens in the coming months, the thawing of relations between Ankara and Moscow will almost certainly prove to be a turning point in the Syrian conflict – and possibly for the whole power dynamics of the Middle East.

Source : http://www.thecanary.co/2016/08/10/the-ticking-time-bomb-causing-big-problems-for-the-west-in-syria/

Islam in Kazakhstan

Islam is the largest religion practiced in Kazakhstan, as 70.2% of the country's population is Muslim according to a 2009 national census.[1] Ethnic Kazakhs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school.[2] There are also small number of Shia and few Ahmadi Muslims.[3] Geographically speaking, Kazakhstan is the northernmost Muslim-majority country in the world. Kazakhs make up over half of the total population, and other ethnic groups of Muslim background include Uzbeks, Uyghurs and Tatars.[4] Islam first arrived on the southern edges of the region in the 8th century from Arabs.

History

Islam was brought to the Kazakhs during the 8th century when the Arabs arrived in Central Asia. Islam initially took hold in the southern portions of Turkestan and thereafter gradually spread northward.[5] Islam also took root due to the zealous missionary work of Samanid rulers, notably in areas surrounding Taraz[6] where a significant number of Kazakhs accepted Islam. Additionally, in the late 14th century, the Golden Horde propagated Islam amongst the Kazakhs and other Central Asian tribes. During the 18th century, Russian influence rapidly increased toward the region. Led by Catherine, the Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the region to preach to the Kazakhs whom the Russians viewed as "savages" and "ignorant" of morals and ethics.[7][8]

Russian policy gradually changed toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[9] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly elite Russian military institutions.[9] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring religious fervor by espousing pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[10] During the Soviet era, Muslim institutions survived only in areas where Kazakhs significantly outnumbered non-Muslims due to everyday Muslim practices.[11] In an attempt to conform Kazakhs into Communist ideologies, gender relations and other aspects of the Kazakh culture were key targets of social change.[8]

In more recent times, Kazakhs have gradually employed determined effort in revitalizing Islamic religious institutions after the fall of the Soviet Union. While not strongly fundamentalist, Kazakhs continue to identify with their Islamic faith,[12] and even more devotedly in the countryside. Those who claim descent from the original Muslim warriors and missionaries of the 8th century, command substantial respect in their communities.[13] Kazakh political figures have also stressed the need to sponsor Islamic awareness. For example, the Kazakh Foreign Affairs Minister, Marat Tazhin, recently emphasized that Kazakhstan attaches importance to the use of "positive potential Islam, learning of its history, culture and heritage."[14]

Soviet authorities attempted to encourage a controlled form of Islam under the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan as a unifying force in the Central Asian societies, while at the same time prohibiting true religious freedom. Since independence, religious activity has increased significantly. Construction of mosques and religious schools accelerated in the 1990s, with financial help from Turkey, Egypt, and, primarily, Saudi Arabia.[15] In 1991 170 mosques were operating, more than half of them newly built. At that time an estimated 230 Muslim communities were active in Kazakhstan.

Islam and the state

In 1990 Nursultan Nazarbayev, then the First Secretary of the Kazakhstan Communist Party, created a state basis for Islam by removing Kazakhstan from the authority of the Muslim Board of Central Asia, the Soviet-approved and politically oriented religious administration for all of Central Asia. Instead, Nazarbayev created a separate muftiate, or religious authority, for Kazakh Muslims.[16]

With an eye toward the Islamic governments of nearby Iran and Afghanistan, the writers of the 1993 constitution specifically forbade religious political parties. The 1995 constitution forbids organizations that seek to stimulate racial, political, or religious discord, and imposes strict governmental control on foreign religious organizations. As did its predecessor, the 1995 constitution stipulates that Kazakhstan is a secular state; thus, Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian state whose constitution does not assign a special status to Islam. Though, Kazakhstan joined the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in the same year. This position was based on the Nazarbayev government's foreign policy as much as on domestic considerations. Aware of the potential for investment from the Muslim countries of the Middle East, Nazarbayev visited Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia; at the same time, he preferred to cast Kazakhstan as a bridge between the Muslim East and the Christian West. For example, he initially accepted only observer status in the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), all of whose member nations are predominantly Muslim. The president's first trip to the Muslim holy city of Mecca, which occurred in 1994, was part of an itinerary that also included a visit to Pope John Paul II in the Vatican.[16]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)